The Author Signal: Nietzsche’s Typewriter and Medium Theory

|

| Malling-Hansen Writing Ball |

Friedrich Nietzsche stands as one of the most influential philosophers of the 19th century, whose radical critique of truth, morality and knowledge continues to shape contemporary thought. His works, including Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1883-1885), Beyond Good and Evil (1886) and On the Genealogy of Morals (1887), challenged Western philosophical and cultural traditions through a sustained critique of metaphysical thinking and rationalist epistemology. Through concepts such as the will to power, eternal recurrence and the death of God, Nietzsche developed a philosophical project aimed at overturning assumptions about knowledge and truth. His deteriorating health, particularly his declining eyesight, forced him to confront not just philosophical questions about knowledge but also the material conditions of its production. This embodied experience of technological mediation led Nietzsche to recognise how thought itself is shaped by its means of production. His encounter with the typewriter therefore represents a crucial moment where philosophical critique intersects with technological transformation of consciousness. The typewriter became both a practical necessity and a concrete example of how technological systems reorganise cognitive processes and knowledge production. This intersection between bodily limitation, technological prosthesis and philosophical thought makes Nietzsche's encounter with the typewriter particularly significant for understanding how inscription technologies transform modes of thinking.

One of the more poignant moments in Nietzsche’s long and tormented career was when the catalogue of his many ailments, both mental and physical, started to include encroaching blindness. To remedy that he turned to experimentation with the (very primitive) typewriters of the time in 1882 – a Malling-Hansen Writing Ball. This was a major crisis in his writing as he had to accustom himself to what must have seemed almost an entirely new medium and led him to confess that “our writing tools are also working on our thoughts” (quoted in Kittler 1999). Nietzsche, who had dreamed of a machine that would transcribe his thoughts, choose the machine whose "rounded keyboard could be used exclusively through the sense of touch because on the surface of the sphere each spot is designated with complete certainty by its spatial position" (Kittler 1992: 193). Indeed, as Carr (2008) argues "once he had mastered touch-typing [with the new typewriter], he was able to write with his eyes closed, using only the tips of his fingers. Words could once again flow from his mind to the page." The condition of possibility created by a particular medium forms an important part of the theoretical foundations of medium theory, which questions the way in which medial changes lead to epistemic changes. This has become an important area of inquiry in relation to the differences introduced by computation and digital media, more generally (see Berry 2011). Indeed, in Nietzsche's case,

Nietzsche’s case seemed somewhat more promising as his attempts at typewriting were not only commented on by him but also made at a very early stage of mechanical text production – and at the overlap between discourse networks (Kittler 1992: 193). Although Nietzsche is thought to have only used the typewriter for a short period during 1882, an experiment claimed to have lasted either weeks (Kittler 1992), or up to a couple of months (Kittler 1999: 206) – although Günzel and Schmidt-Grépály (2002) more concretely state he typed between February to March 1882 when Nietzsche was also finishing The Gay Science. In fact, Nietzsche produced a collection of typed works he titled 500 Aufschriften auf Tisch und Wand: Für Narrn von Narrenhand. Nietzsche himself commented, “after a week [of typewriting practice,] the eyes no longer have to do their work” (Kittler 1999: 202).[1] Indeed, the technological shock may have been much stronger here than in the case of James or of authors who, some twenty years ago, enthusiastically exchanged white correction fluid for the word-processor delete button and cut-and-paste. Using the typewriter, Nietzsche’s prose “changed from arguments to aphorisms, from thoughts to puns, from rhetoric to telegram style” (Kittler 1999: 203). Indeed, Kittler argues that,

The turning point for Kittler (1999) is represented by The Genealogy of Morals which was written in 1887 – by now Nietzsche was forced by continued poor vision to use secretaries to record his words. Here, it is argued that Nietzsche elevated the typewriter itself to the "status of a philosophy," suggesting that "humanity had shifted away from its inborn faculties (such as knowledge, speech, and virtuous action) in favor of a memory machine. [When] crouched over his mechanically defective writing ball, the physiologically defective philosopher [had] realize[d] that 'writing . . . is no longer a natural extension of humans who bring forth their voice, soul, individuality through their handwriting. On the contrary, . . . humans change their position – they turn from the agency of writing to become an inscription surface'" (Winthrop-Young and Wutz 1999: xxix).

In the very tentative analysis presented here (and which must be redone with a greater collection of Nietzsche’s works), the standard stylometric procedure of comparing normalized word frequencies of the most frequent words in the corpus was applied by means of the “stylo” (ver. 0-4-7) script for the R statistical programming environment (Eder and Rybicki 2011).

The script converts the electronic texts to produce complete most-frequent-word (MFW) frequency lists, calculates their z-scores in each text according to the Delta procedure (Burrows 2002); uses the top frequency lists for analysis; performs additional procedures for better accuracy (including Hoover’s culling, the removal of all words that do not appear in all the texts for better independence of content); compares the results for individual texts; produces Cluster Analysis tree diagrams that show the distances between the texts; and, finally, combines the tree diagrams made for various parameters (number of words used in each individual analysis) in a bootstrap consensus tree (Dunn et al. 2005, quoted in Baayen 2008: 143-147). The script, in its ever-evolving versions, is available online (Eder, Rybicki and Kestemont 2012). The consensus tree approach, based as it is on numerous iterations of attribution tests at varying parameters, has already shown itself as a viable alternative to single-iteration analyses (Rybicki 2012, Eder and Rybicki 2012).

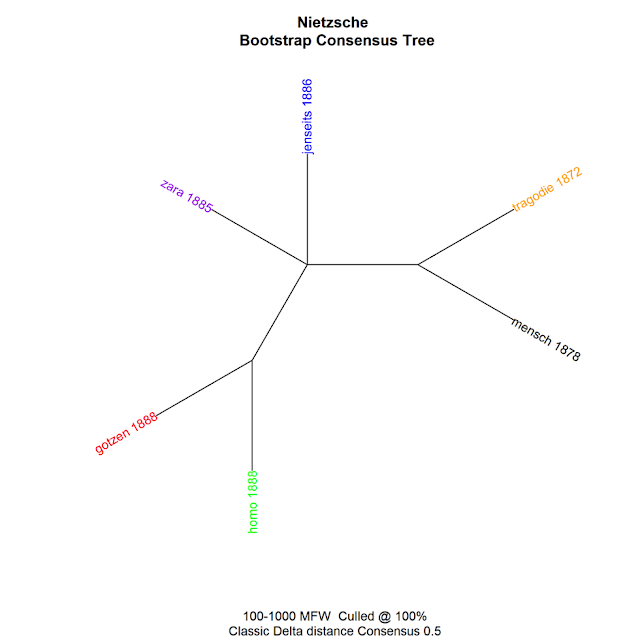

The first analysis was performed for complete texts of six works by Nietzsche: Die Geburt der Tragödie (1872) and Menschliches, Allzumenschliches (1878), both written before 1879, his “year of blindness,” and his typewriter experiments of 1882, and Also sprach Zarathustra (1883-5), Jenseits von Gut und Böse (1886), Ecce homo and Götzen-Dämmerung (1888). The resulting graph suggest a chronological evolution of Nietzschean style as the early works cluster to the right, and the later ones to the left of Figure 1.

Notes

[1] According to Günzel and Schmidt-Grépály (2002), Nietzsche typed 15 letters, 1 postcard and 34 bulk sheets (including some poems and verdicts) with his 'Schreibkugel' from Malling-Hansen in 1882.

Berry, D. M. (2012) The Social Epistemologies of Software, Social Epistemology: A Journal of Knowledge, Culture and Policy, 26:3-4, 379-398

Emden, C. (2005) Nietzsche On Language, Consciousness, And The Body, University of Illinois Press.

Günzel, S. and Schmidt-Grépály, R. (2002) (eds.) Friedrich Nietzsche. Schreibmaschinentexte, 2nd edition, Weimar: Verlag der Bauhaus Universität, accessed 19/12/2012, http://www.momo-berlin.de/Nietzsche_Schreibmaschinentexte.html

Winthrop-Young, G. and Wutz, M. (1999) Translators' Introduction, in Kittler, F. A., Gramophone, Film, Typewriter, Standford University Press.

One of Nietzsche’s friends, a composer, noticed a change in the style of his writing. His already terse prose had become even tighter, more telegraphic. “Perhaps you will through this instrument even take to a new idiom,” the friend wrote in a letter, noting that, in his own work, his “‘thoughts’ in music and language often depend on the quality of pen and paper.”... “You are right,” Nietzsche replied, “our writing equipment takes part in the forming of our thoughts” (Carr 2008).Stylistics and perhaps above all its younger and computerized daughter, stylometry, have already attempted to find stylistic or stylometrical traces (the "author signal") of similar changes in writing practices by authors – with little positive result. The case of Henry James’s move from handwriting (typewriting) to dictation in the middle of What Maisie Knew has been studied by Hoover (2009). Yet, according to the NYU professor, the author of The Ambassadors took this sudden change in his stride and, despite the fact that we know exactly where the switch occurred, stylometry has been helpless in this case; or, rather, can show no sudden shift in James’s stylistic evolution that continues throughout his career (Hoover 2009). In a way, a similar problem was addressed by Le, Lancashire, Hirst and Jokel (2011) in their study of possible symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease in Agatha Christie word usage and to confirm the same diagnosis in Iris Murdoch. From another perspective, many studies exist on various authors’ switch from handwriting or typing to word processing (see also Lev Manovich's [2008] work on cultural analytics).

|

| Letter from Friedrich Nietzsche to Heinrich Köselitz, Geneva, Feb 17, 1882. Earliest typewriter-written text by Nietzsche still in existence. |

Neitzsche's reasons for purchasing a typewriter were very different from those of his colleagues who wrote for entertainment purposes, such as Twain, Lindau, Amytor, Hart, Nansen, and so on. They all counted on increased speed and textual mass production; the half-blind, by contrast, turned from philosophy to literature, from rereasing to a pure, blind, and intransitive act of writing (Kittler 1999: 206).In other words, the inscription technologies of Nietzsche's time have contributed to his thinking. Nevertheless for Nietzsche the typewriter was "more difficult than the piano, and long sentences were not much of an option" (Emden 2005: 29). Although after his failed experimentation with the typewriter, he remained enthralled by its possibilities – "the assumed immediacy of the written word... seemingly connected in a direct way to the thoughts and ideas of the author through the physical movement of the hand... was displaced by the flow of disconnected letters on a page, one as standardized as another" (Emden 2005: 29).

The turning point for Kittler (1999) is represented by The Genealogy of Morals which was written in 1887 – by now Nietzsche was forced by continued poor vision to use secretaries to record his words. Here, it is argued that Nietzsche elevated the typewriter itself to the "status of a philosophy," suggesting that "humanity had shifted away from its inborn faculties (such as knowledge, speech, and virtuous action) in favor of a memory machine. [When] crouched over his mechanically defective writing ball, the physiologically defective philosopher [had] realize[d] that 'writing . . . is no longer a natural extension of humans who bring forth their voice, soul, individuality through their handwriting. On the contrary, . . . humans change their position – they turn from the agency of writing to become an inscription surface'" (Winthrop-Young and Wutz 1999: xxix).

In the very tentative analysis presented here (and which must be redone with a greater collection of Nietzsche’s works), the standard stylometric procedure of comparing normalized word frequencies of the most frequent words in the corpus was applied by means of the “stylo” (ver. 0-4-7) script for the R statistical programming environment (Eder and Rybicki 2011).

The script converts the electronic texts to produce complete most-frequent-word (MFW) frequency lists, calculates their z-scores in each text according to the Delta procedure (Burrows 2002); uses the top frequency lists for analysis; performs additional procedures for better accuracy (including Hoover’s culling, the removal of all words that do not appear in all the texts for better independence of content); compares the results for individual texts; produces Cluster Analysis tree diagrams that show the distances between the texts; and, finally, combines the tree diagrams made for various parameters (number of words used in each individual analysis) in a bootstrap consensus tree (Dunn et al. 2005, quoted in Baayen 2008: 143-147). The script, in its ever-evolving versions, is available online (Eder, Rybicki and Kestemont 2012). The consensus tree approach, based as it is on numerous iterations of attribution tests at varying parameters, has already shown itself as a viable alternative to single-iteration analyses (Rybicki 2012, Eder and Rybicki 2012).

The first analysis was performed for complete texts of six works by Nietzsche: Die Geburt der Tragödie (1872) and Menschliches, Allzumenschliches (1878), both written before 1879, his “year of blindness,” and his typewriter experiments of 1882, and Also sprach Zarathustra (1883-5), Jenseits von Gut und Böse (1886), Ecce homo and Götzen-Dämmerung (1888). The resulting graph suggest a chronological evolution of Nietzschean style as the early works cluster to the right, and the later ones to the left of Figure 1.

Yet the pattern above shares the usual problem of multivariate graphs for just a few texts: a possibility of randomness in the order of clusters. This is why it makes sense to perform another analysis, this time on the above texts divided into equal-sized segments (10,000 words is usually safe). Figure 2 confirms the chronological evolution pattern as the segments of each individual book are correctly clustered together.

What is more, the previous result is corroborated by a very similar pattern in terms of creation date.

|

| Figure 2, chronological evolution pattern as segments of each individual book are clustered together |

The empirical evidence from stylometric analysis provides support for theoretical claims about how technological mediation transforms consciousness and cognitive processes. These quantitative patterns suggest structural changes in Nietzsche's writing that correspond to shifts in his technological means of inscription. Where Kittler theorised that the typewriter fundamentally altered Nietzsche's thought processes, the computational analysis demonstrates measurable changes in linguistic patterns and textual organisation. This empirical confirmation is significant for understanding how contemporary computational systems similarly reorganise knowledge production and cognitive capacities. The stylometric evidence suggests that technological mediation operates at a deeper structural level than mere content, reshaping the very patterns through which thought is articulated. This finding has interesting implications for analysing how current digital technologies and algorithmic systems may be transforming consciousness in ways that remain partially invisible to traditional modes of analysis. The empirical patterns thus support theoretical arguments about how inscription technologies reorganise both thought and knowledge production through their material affordances and constraints.

The computational analysis of Nietzsche's stylistic transformations reveals more than mere statistical patterns. It helps us see how inscription technologies reorganise thought processes and knowledge production. Through using computational techniques to analyse historical textual changes, we can uncover traces of how media systems transform cognitive capacities. This speaks directly to contemporary concerns about how algorithmic systems and computational infrastructures are restructuring consciousness. When digital technologies mediate knowledge production, they introduce new patterns of thought and cognitive organisation. The stylometric evidence of changes in Nietzsche's writing provides possible empirical support for examining how today's computational systems may be transforming human cognitive capabilities and epistemological frameworks in ways that are not immediately apparent. Just as the typewriter introduced new forms of textual production and thought for Nietzsche, contemporary digital media are reorganising how knowledge is created, circulated and understood.

As has been said above, a greater number of texts is needed to confirm these initial findings. There is indeed a clear division of Nitzschean style into early and late(r). Whether this is a repetition of a phenomenon observed in many other writers (Henry James, for one), or a direct impact of technological change and therefore a confirmation of the claims of medium theory, remains to be investigated. Nonetheless, this approach offers an additional method to explore how medial change can be mapped in relation to changes in knowledge. It also offers a potential means for exploring the way in which contemporary debates over the introduction of computational and digital means of creating, storing and distributing knowledge affect the way in which authorship itself is undertaken.

This doesn't just have to be strictly between mediums, and there is potential for exploring intra-medial change and the way in which writing has been influenced by the long dark ages of Microsoft Word as the hegemonic form of digital writing (1983-2012), and which gradually appears to be coming to an end in the age of locative media, apps, and real-time streams. Indeed, with exploratory digital literature forms, represented in ebooks, computational document format (CDF) and apps, such as Tapestry, which allow the creation of "tap essays" (Gannes 2012), new ways of authoring and presenting knowledge are suggested. Only a short perusal of Apple iBooks Author, for example, shows the way in which the paper forms underlying the digital writings of the 20th Century, are giving way to new ways of writing and structuring text within the framework of a truly digital medium made possible through tablet computers, smart phones and the emerging "tabs, pads and boards" three-screen world.

Contemporary digital inscription technologies are fundamentally reorganising knowledge production and cognitive processes. The emergence of computational documents, real-time streams and algorithmic writing systems represents more than simply new technical affordances. These technologies constitute a profound transformation in how knowledge is created, stored and circulated. Where Nietzsche encountered the typewriter as a novel form of textual production, we now face automated systems that can generate text, analyse writing patterns and reshape authorship itself. The tablet computer, the smartphone and the emerging computational ecology of 'tabs, pads and boards' signal a decisive break with paper-based forms of knowledge organisation that dominated the 20th century.

These changes in inscription technologies parallel broader transformations in computational culture. The relational database, object-oriented programming and algorithmic processing increasingly structure how knowledge is organised and understood. This computational reorganisation of knowledge extends beyond mere technical changes to reshape cognitive capacities and epistemological frameworks. Just as Nietzsche's encounter with the typewriter altered his writing style and thought processes, contemporary computational systems are transforming how we think, write and know. Kittler clearly foresaw an important turn in the way in which we should research and understand these processes, writing,

To put it plainly: in contrast to certain colleagues in media studies, who first wrote about French novels before discovering French cinema and thus only see the task before them today as publishing one book after another about the theory and practice of literary adaptations... In contrast to such cheap modernisations of the philological craft, it is important to understand which historical forms of literature created the conditions that enabled their adaptation in the first place. Without such a concept, it remains inexplicable why certain novels by Alexandre Dumas, like The Three Musketeers, have been adapted for film hundreds of times, while old European literature, from Ovid's Metamorphoses to weighty baroque tomes, were simple non-starters for film... It is possible... to conclude from the visually hallucinatory ability that literature acquired around 1800 that a historically changed mode of perception had entered everyday life. As we know, after a preliminary shock Europeans and North Americans learned very quickly and easily how to decode film sequences. They realized that film edits did not represent breaks in the narrative and that close-ups did not represent heads severed from bodies. (Kittler 2009: 108)

Equally, today in a world filled with everyday computational media, Europeans and North Americans are learning very quickly to adapt to the real-time streaming media of the 21st Century. We are no longer surprised when live television is paused to make a drink, or our mobile phone tells us that we are running late for a meeting and offers us a quicker route to get to the location. Nor are we perplexed by multiple screens, screens within screens, transmedia storytelling, social media, or even contextual navigation and adaptive user interfaces. Thus new social epistemologies are emerging in relation to computational media, that is, "the conditions under which groups of agents (from generations to societies) acquire, distribute, maintain and update (claims to) belief and knowledge [has changed] through the active mediation of code/software" (Berry 2012: 380). Again, a historically changed mode of perception has entered everyday life, and which we can explore through its traces in cultural artefacts, such as literature, film, television, software and so forth.

Future research must pursue several critical directions in analysing how computational technologies transform knowledge production and cognitive processes. Firstly, we need more sophisticated empirical methods for tracking how digital technologies reorganise thought patterns and writing practices. This requires developing new computational tools that can analyse both historical and contemporary transformations in knowledge production. Secondly, the political economy of computational knowledge systems requires further investigation, particularly regarding how algorithmic processes standardise and automate cognitive labour. Thirdly, we need theoretical frameworks adequate to understanding how automated systems are reshaping consciousness and epistemological frameworks. This includes examining how automated knowledge production systems transform traditional notions of authorship and creativity. Finally, we must develop new conceptual tools for analysing how computational mediation affects cognitive processes at both individual and collective levels. Understanding these transformations requires sustained investigation of how technological systems reshape thought itself through their material affordances and constraints.

With the suggestive analysis offered in this short article, we hope to have demonstrated how computational approaches can create research questions in relation to medium theory, and which although not necessary offering conclusive results, nonetheless press us to explore further the links between medial and epistemic change.

David M. Berry and Jan Rybicki

Notes

[1] According to Günzel and Schmidt-Grépály (2002), Nietzsche typed 15 letters, 1 postcard and 34 bulk sheets (including some poems and verdicts) with his 'Schreibkugel' from Malling-Hansen in 1882.

Bibliography

Berry, D. M. (2011) The Philosophy of Software: Code and Mediation in the Digital Age, London: Palgrave.

Berry, D. M. (2012) The Social Epistemologies of Software, Social Epistemology: A Journal of Knowledge, Culture and Policy, 26:3-4, 379-398

Burrows, J.F. (2002) “Delta: A Measure of Stylistic Difference and a Guide to Likely Authorship,” Literary and Linguistic Computing 17: 267-287.

Carr, N. (2008) Is Google Making Us Stupid?, The Atlantic, accessed 19/12/2012, http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2008/07/is-google-making-us-stupid/306868/

Dunn, M., Terrill, A., Reesink, G., Foley, R.A. and Levinson, S.C. (2005) “Structural Phylogenetics and the Reconstruction of Ancient Language History,” Science 309: 2072-2075. Quoted in Baayen, R.H. (2008) Analyzing Linguistic Data. A Practical Introduction to Statistics using R, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Eder, M. and Rybicki, J. (2011). Stylometry with R. Stanford: Digital Humanities 2011.

Eder, M. Rybicki, J., and Kestemont, M. (2012). Computational Stylistics, accessed 19/12/2012, http://sites.google.com/site/computationalstylistics

Eder, M. and Rybicki, J. (2012). “Do Birds of a Feather Really Flock Together, or How to Choose Test Samples for Authorship Attribution,” Literary and Linguistic Computing, First published online August 11, 2012: 10.1093/llc/fqs036.

Emden, C. (2005) Nietzsche On Language, Consciousness, And The Body, University of Illinois Press.

Gannes, L. (2012) When an App Is an Essay Is an App: Tapestry by Betaworks , Wall Street Journal, http://allthingsd.com/20121106/when-an-app-is-an-essay-is-an-app-tapestry-by-betaworks/

Günzel, S. and Schmidt-Grépály, R. (2002) (eds.) Friedrich Nietzsche. Schreibmaschinentexte, 2nd edition, Weimar: Verlag der Bauhaus Universität, accessed 19/12/2012, http://www.momo-berlin.de/Nietzsche_Schreibmaschinentexte.html

Kittler, F. A. (1992) Discourse Networks, 1800/1900, Stanford University Press.

Kittler, F. A. (1999) Gramophone, Film, Typewriter translated by Geoffrey Winthrop-Young and Michael Wutz, Stanford: Standford University Press, 200-208, quoted in Patricia Falguières, “A Failed Love Affair with the Typewriter”, rosa b, accessed 19/12/2012, http://www.rosab.net/spip.php?page=article&id_article=47#nb1

Kittler, F. A. (2009) Optical Media, London: Polity Press.

Hoover, David L. (2009) “Modes of Composition in Henry James: Dictation, Style, and What Maisie Knew,” Digital Humanities 2009, University of Maryland, June 22-25.

Le, X., Lancashire, I., Hirst, G., and Jokel, R. (2011) “Longitudinal detection of dementia through lexical and syntactic changes in writing: a case study of three British novelists,” Literary and Linguistic Computing, 26(4): 435-461

Manovich, L. (2008) Cultural Analytics, accessed 19/12/2012, http://lab.softwarestudies.com/2008/09/cultural-analytics.html

Rybicki, J. (2012) “The Great Mystery of the (Almost) Invisible Translator: Stylometry in Translation.” In Oakes, M., Ji, M. (eds). Quantitative Methods in Corpus-Based Translation Studies, Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Winthrop-Young, G. and Wutz, M. (1999) Translators' Introduction, in Kittler, F. A., Gramophone, Film, Typewriter, Standford University Press.

Comments

Post a Comment